Cartographies Of The Very Curious

Cities as Cabinets of Curiosities, Urban Metaphors, Lovers of Neptune’s Cabinet

Hi! I’m Patricia Hurducaș, a Romanian writer and urban explorer currently based in The Hague. I write about places, imagination, life abroad, and through this newsletter, The Flâneurs Project, I try to map through essays and interviews the evolving relationships we form with the places we inhabit, leave behind, or long for.

December 9, 1967

A THING

I saw a thing. A real thing. It was ten o’clock at night in Praça Tiradentes and the taxi was moving pretty fast. Then I saw a street I will never forget. I’m not going to describe it: it’s mine. All I can say is: it was empty and it was ten o’clock at night. Nothing more. But the seed had been planted.

— Clarice Lispector, Selected Crônicas

“A metaphor is not an ornament. It is an organ of perception.”

— Neil Postman

There are plenty of metaphors we use for a city: the Green Heart, the rotten tooth, psychic prison, brain, organism, machine, labyrinth, garden, sanctuary, dream. Metaphors are powerful. They summon entire worlds in just a few words, stretching our imagination beyond what we previously perceived.

In a paper called Metaphor and urban studies-a crossover, theory and a case study of SS Rotterdam, Peter Nientied examines whether Gareth Morgan’s eight organizational metaphors can also describe cities. These metaphors include the machine, the organism, the brain, culture, the political system, the psychic prison, flux and the instrument of domination. Metaphors do more than shape language. They shape how we think, how we move through cities and how we understand the world around us.

On a recent visit to Leiden, a small city ten minutes away by train from The Hague, I couldn’t help but compare this city to a Kunstkammer, a cabinet of curiosities. My experience of it always stretched my imagination and satisfied something within me. I find different worlds scattered along my walks, and the closer I look at them, the more they multiply into other worlds of their own.

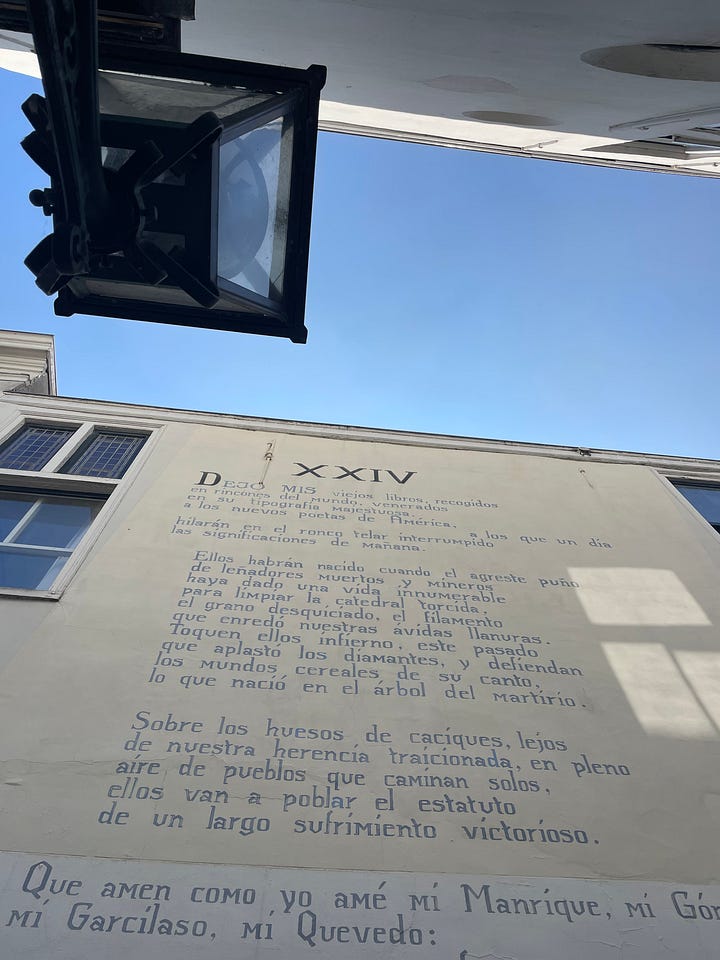

To give an example, I started my walk facing Pablo Neruda’s poem Testament II, one of the 100 poems displayed on the buildings of this city. I tried to capture and understand the essence of the poem, but my Spanish is rusty, so what struck me at first glance was the beginning:

“Dejo mis viejos libros, recogidos / en rincones del mundo, venerados / en su tipografía majestuosa, / a los nuevos poetas de América”

“I leave my old books, gathered / from the corners of the world, / revered for their majestic typography, / to the new poets of America.”

I let those lines sink in and think about testaments as I make my way into the Saturday market – a feast of colours, smells, and movement.

Slowly, I am lured into a bookstore, one I haven’t visited before, and all my present world is shattered yet again into other worlds, a multitude of them, all of them reviving parts of my imagination. I’m completely hooked and revitalized, and my eyes fall on Shell Shock, a book about conchological curiosities. I’ve been obsessing over shells in the past months, and here it is – a physical testament that shells proved to be obsessions for other people as well.

I move my fingers over photos of paintings of shells as I learn about the Lovers of Neptune’s Cabinet, a group of six shell collectors from the early 18th century. They met once a month in Dordrecht, Holland - about an hour from my home - to discuss their hobby and possible swaps. I look them up online, but there is no information about this group, apart from an art exhibition years ago in Adelaide, Australia, that mentions their name. There is still so much knowledge that can only be found by stumbling upon books in second‑hand bookstores, not online.

As I do some research, I find another group: Foundation Creature Shell, a group of Dutch collectors based in Utrecht with a collection of over 63,000 items, most of them donated today to museums across the Netherlands. I keep wondering what drives us to collect things, and what drives fascination into a lifelong search and ritual of collecting.

I return to The Hague and I remember a special place I visited just once, the type of place that’s very rare to find these days outside museums: Het Rariteiten Kabinet, a cabinet of curiosities. The shop, which resembles a very unique gallery, is owned by Loek Dekkers, known for his unique collection of natural history objects, ethnographic items, and rare gifts from nature. In my short visit there, I eyed one of the most beautiful shells I’ve seen – a white translucent shell with a faint shade of purple, resembling in shape a Diadema melon shell.

The owner and I strike up a short conversation, and I ask about the music playing in the shop, as it feels comfortably hypnotic. “Armand Amar,” he says, asking if I have watched the documentary Human. I take down notes, not to forget. I return home curious to make connections between everything I’ve come across.

Not all cities and places are designed to feed human curiosity. But the ones that are - those designed as multilayered worlds, as bridges to the past, posing questions to the future, and holding a mysterious, curious layer in the present - can rewire how we see the world.

And I hope that as we walk through these cities and these places, we find ourselves, little by little, transformed by something hard to put into words, something wholly ours, as Clarice Lispector once described in one of her crônicas.

A note in case we cross paths in the near future:

I’ll be in Cluj-Napoca, Romania, from May 29 to June 2 to host a Flâneurs Project weekend gathering; in London on June 25, where I plan to host a salon; and in Wimborne St. Giles for the Realisation Festival from June 26 to 29.

Thank you for reading. As always, I welcome your emails, notes, stories.

Onwards,

Patricia